…perhaps I am looking at living maps that outline a way of emotionally and

…perhaps I am looking at living maps that outline a way of emotionally and

facially navigating any listening experience…

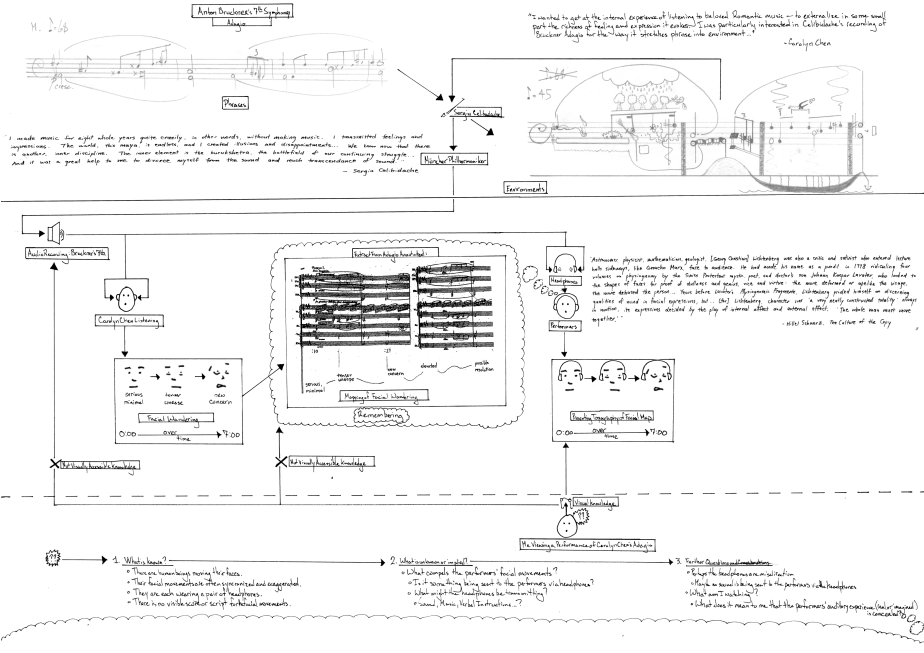

On the face of it, Carolyn Chen’s Adagio is a deceptively simple piece. A performance of the piece presents three or four performers wearing headphones and making slow-motion facial expressions over the course of seven minutes. Seemingly absurd, Chen’s piece is perplexing and has challenged me to think anew the dynamic relationships between facial expressions, slow-motion movement, copying, and private/public activities of listening.

To be more specific about what is going on during a performance of Adagio:

- A group of performers listen

- They listen while wearing headphones

- They listen to sounds being sent through headphones

- For each performance those sounds take the reliable and reproducible form of an excerpted recording of Sergiu Celibidache’s remarkably slow expansion of Anton Bruckner’s adagio from his 7th Symphony

- While listening, the performers slowly move their faces (each an assemblage and territory of emotional expressions) in tandem with the recording

- Their facial movements translate, project, and give body to a simultaneously private and communal experience, amongst the performers anyways, of listing to Celibidache’s recording wherein “phrase [is stretched] into environment”

- Their facial expressions wander through a Romantic environment

Because the headphones conceal the sound of the recording and Carolyn’s facial guide is memorized/embodied, during the performance an audience is confronted with an ‘incomplete’ picture of the work. The diagram above [click to expand] is designed to illustrate not only the intricacies of the work that underlie the construction and performance of Adagio, but also serves to represent terminology I have adopted in constructing a response to what I think is a fascinating question that this piece poses: What might it mean to an audience to be presented with powerfully evocative expressive and emotive facial expressions that are unexplained, where headphones privatize listening experiences and paradoxically tether facial expressions to the implication of sound (an idea of listening) and the external reality of silence?

In my search for an answer to this question, I started thinking through an idea I had that a presentation of this piece is an invitation to participate in voyeuristic listening, a following of someone’s private and intimately emotional and facial relationship with some assumed sonic referent. Relatedly, I contemplated the idea that the piece excavates bodily listening practices and reflects them back onto the audience. However, my readings of Chen’s piece subordinated the foregrounded facial expressions to an assumed and precise sonic referent, ignoring the fact that an ontologically discernible aural reality has been deliberately obfuscated by the use of headphones. Instead of assuming that the headphones signify some specific sonic referent, I became interested in the idea the headphones could more generally signify a type of personal listening experience detached from any particular sounds. To me, this shift in emphasis from facial expressions being beholden to some particular listening experience restores primacy to the facial expressions and imbues their movements with a sense of agency.

It seems appropriate to focus on the facial aspect of Adagio given the fact that a performance of the piece is essentially a retracing of Chen’s facial wandering through her listening of Bruckner’s music. In conversation with Chen, she describes her attraction to Celibidache’s interpretation of Bruckner for the way that phrases are stretched into environments. In making Adagio I imagine Chen facially wandering through the Romantic landscape of Bruckner, retrospectively making notes from her journeys, and mapping those journeys onto Bruckner’s score to form a guided dérive for other people. By withholding the exact musical terrain trekked during a performance of Adagio and presenting only the performers’ facial movements, I have the sense that the piece presents an audience with of a living map for grafting, through emotional and facial steps, leaps, pauses, distractions and fascinations, the terrain of Celibidache’s environment onto the general experience of listening. The performers of Adagio become scores for future listening experiences. This is a model of listening where faces hear and modulate their environment.

To illustrate the full ramifications of this idea, I offer an anecdote recounted by Guy Debord about “a friend [who] had just wandered through the Harz region of Germany while blindly following the directions of a map of London.” To be clear, what I am suggesting is that a performance of Adagio could be détourned, read, and utilized as a psychogeographic map for listening to any other musical or sonic landscape in resonance with another human’s facial wandering through one of Bruckner’s sonic cathedrals. For me at least, this reading makes sense of the seemingly absurd situation of a ‘loud silence’ in Adagio. It expands what the piece means to me; it expands my appreciation of the facial facets of performance in general; and, perhaps most importantly, makes me excited to present this work for an audience of other thinkers, movers, and feelers who will undoubtedly respond to the piece in their own unique way.

Come and pour over Chen’s map at performances on 23rd April in London and 30th April in Manchester and let me know what you think afterwards. In the meantime, you can watch Chen alongside Clint McCallum and Ian Power as they perform Adagio in the video embedded above. And if you’re interested in giving my proposition of the piece a test, you may find it interesting to mute the video (to remove background hiss) and listen to some other music or sounds of your choosing while copying one (or all) of the performers’ facial expressions…

Or perhaps you’d like to try my proposition with this equally intriguing video made by Ensemble DieOrdnungDerDinge in preparation for performances of Chen’s Adagio in which they wander through an excerpt of Richard Strauss’ Also sprach Zarathustra:

-Michael Baldwin

2 thoughts on “Better Know A Weisslich: Carolyn Chen’s Adagio”